A Personal Essay

By Sonam Yangzom

In 2010, I moved to the cities to study on a scholarship granted by Pestalozzi

Children’s Village Society. I still remember how my parents’ faces were glowing

with unadulterated affection and joy while looking at the letter of acceptance. I

was happy but nervous. They were happy but sad that I would be gone. And

together we were brimming with a paradox of feelings. I did not realize the

gravity of the opportunity then. I was just a tiny 10 year old mountain girl ready

to conquer the world under my reha. I remember being excited about wearing

uniform from head to toe; ribbons, blue tie, white shirt, blue skirt, white socks,

black shoes and a colourful bottle around my head. My little head danced around

these colours and imaginations.

My father travelled with me to the new place I would call my own in a few days.

That was my first time travelling out of Spiti, observing completely different

landscapes, different architecture, different ways of living. I was awed,

wonderstruck; my little eyes were impressed. Finally I was seeing something

beyond mountains, hearing something beyond the bleating of goats. In the cities

or in my new abode, people bathed every day or every alternate day. It was so hot

you had to unless you wished to smell like a rotten turnip. When I went to the

roof I could not see the Himalayas. I could only see the vast sky with nothing but

tall buildings below it as far as my eyes could see. I had a room which I shared

with five other girls. It was called the Cherries Room. I learnt that Cherry was a

fruit. I still remember how I wondered what cherries taste like. Back in my

hometown Spiti, cherries are never talked about, leave alone growing them and

seeing them in the vegetable markets. The cold and dry climate is very partial. It

only allows green peas, barley and black peas to thrive.

In my new abode, we had pour-flush toilets, so different from the traditional

toilets back home. I wondered where my shit went. It just got flushed and

disappeared. It must go down the sewers and then where. I didn’t know how the

septic tanks got cleaned, where the wastes finally went. Nobody knew. But you

have no idea how much I was awed by this city life, marked by shiny marble

floors, different sanitation systems and tall buildings. I had already decided in my

mind that this way of life was definitely better than my village life back at home.

I could not think for myself because like everyone else, I was devoured by ideas

of progress and development. I was already in the chains of a society that viewed

a big house, a nice toilet and abandonment of the grip of village life as

benchmarks of a successful life. I could not think for myself. I was just a ten year

old kid who was incapable of thinking beyond these social constructions of

success and progress.

Every time I looked at the tall buildings, it killed a little bit of village life inside

me. I was ashamed to say that I belonged to a very rural village in the Himalayas

with no network connection at all. I was ashamed to say that my parents had to

walk four kilometres to call me every Sunday through a landline phone. And in

winters they had to walk through snow blizzards and two feet of snow. Just to

hear my voice and how I felt in the new modern abode. I would never dare to tell

them that all my mother did in summers was work in the fields, picking weeds

and irrigating fields besides collecting cow dung for winters. My dad worked in

the fields too during the harvesting season of green peas. I would never speak

about how the toilet in my house was because it was nowhere close and

comparable to the shiny pour-flush toilets. Because it wasn’t modern! I realize

now how this mere word ‘modern’ weighed me down, made me feel little,

downplayed the richness of my Spitian life. It just blinded me to all the beauty

and sustainability and peace my Spitian life had to offer. It made me feel like that

was the life I was supposed to leave behind or come out of.

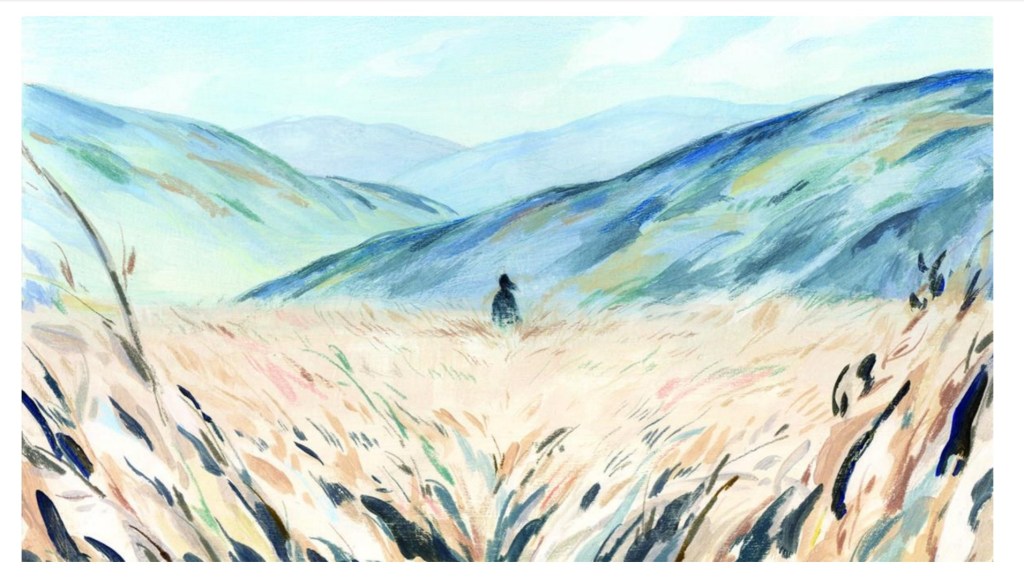

Now I realize what a wrong and distorted trajectory my thoughts had taken. It is

also sad what a distorted and one-dimensional notion of progress we inhabit in

our minds. Living back in my hometown has always been so fulfilling, mentally,

emotionally and spiritually. Life back in Spiti is so simple, so sustainable and so

environmentally friendly. The toilet sanitation system I was ashamed of is so in

sync with nature. We shit. Our shit goes down and decomposes in the thriving

presence of other natural wastes and microorganisms. It becomes manure which

is then used for our fields. In Spiti, most of the households have domesticated

animals who live in the same house as the owners. At the back part of the house

called ra. All the food leftovers of the house are given to the reared animals.

There is no concept of ‘waste’. Spiti has such a rich culture, a sustainable

livelihood and generous people. I think coming to the cities has brought me closer

to what I call my home. It has enlightened me on the paradox of progress that the

current government clothes around everyone. It has made me realize how I would

wake up to goats bleating and horses neighing rather than the honking of cars. I

think I was never made for a very busy city life. I like to take everything slow,

work at my own pace, watch the clouds move through the sky or notice the stream

gleaming in the light of afternoon sunlight. I like to breathe deep and nurture little

seeds of Spitian life in me. Slow, simple and a grounded feeling of coexistence

with nature. I think I was meant to wake up, watch the sun peeking out of the

Himalayas, hear the village shepherd’s call to the domesticated cows and goats;

“Raluk bhalang toen”, have thukpa with my family and set out on my day

routine. But if everything in the world danced to the tunes of your thoughts, what

a boring and disappointing place the world would be to live in.

Spiti gives me the peace of mind I would never get anywhere. It makes me feel

dynamic. It brings me closer to the vastness of nature. It teaches me that progress

should be measured on love , relationships, health and education rather than

architectures, concrete structures, sanitation systems or agricultural practices that

are completely detached from nature. Spiti is my one mere chance at escaping the

draconian hands of capitalism, modernity and technology. It’s about going back

in time beyond the virtual world, beyond highways to narrow trails and mud roads

where you are present with all of your being and feeling everything. The wind.

The sun. And the dust. And I love it for that. Because once in a while, you crave

all parts of you. You crave your roots. You crave the dust in which you grew.

17 APRIL 2020